The history of Paris dates back to approximately 259 BC, with the Parisii, a Celtic tribe settled on the banks of the Seine. In 52 BC, the fishermen village was conquered by the Romans, founding a Gallo-Roman town called Lutetia.

The city changed its name to Paris during the fourth century. During this period, the city was threatened by Attila the Hun and his army, and according to the legend, the inhabitants of Paris resisted the attacks thanks to the providential intervention of Saint Geneviève (patron saint of the city).

In 508 the first king of the Franks, Clovis I, made Paris the capital of his empire. In 987, the Capetian dynasty came to power until 1328.

During the eleventh century, Paris gradually became more prosper thanks to its trade in silver and because it was a strategic route for pilgrims and traders.

Riots and uprisings

At the beginning of the twelfth century, the first university in France was founded thanks to the uprisings of students and professors. Louis IX appointed the chaplain, Robert de Sorbon, to establish the College, which was later named after him, the Sorbonne.

Three insurrections took place during the fourteenth century in Paris: the first, in 1358, when Étienne Marcel led a merchant revolt. The second was a tax riot known as the Maillot uprising in 1382, and the third was the Cabochien revolt in 1413. These riots were part of the Hundred Years’ War.

Additionally, the capital of France, which was the most populated city in Europe in 1328, was struck by the Bubonic plague, killing thousands of Parisians. Following the Hundred Years’ War, Paris was devastated and Joan of Arc was unable to keep the British from taking Paris. In 1431, Henry VI of England was crowned King of France and the English did not leave until 1436.

The city kept on growing during the following centuries, although monarchs preferred to live in the Loire Valley. In 1528, King Francis I returned the royal residence to Paris and the city became the largest in Western Europe.

On 24 August, 1572, the royal council decided to assassinate the leaders of the Protestants (Hugonotes), which lead to Catholic mobs butchering protestants in Paris. Known as St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, it spread from Paris to the rest of the country during the following months.

Margaret of Valois, sister of King Charles IX, married Henri of Navarre (Head of the Huguenots dynasty) that same year, while Henry III tried to find a solution to the conflicts between the Catholics and Protestants. However, in 1588, the French Catholics forced Henry III to flee on the so-called Day of the Barricades and killed him a year later. He was succeeded by Henry of Navarre, becoming King Henry IV. A decade later, Henry IV decided to convert to Catholicism and was crowned King of France in 1594.

In 1648, the second Day of the Barricades took place when the Parisians opposed the King due to the deplorable level of poverty. This was the beginning of a long uprising called the Fronde parlementaire, a serie of civil wars that took place in France between 1648 and 1662. Fifteen years later, King Louis XVI moved the royal residence to Versailles.

The decline of the Monarchy

As a consequence of the Fronde, poverty spread throughout Paris. During this period, there was an explosion of the Enlightenment philosophical movement, whose principles are based on reason, equality and freedom.

Philosophers and authors such as Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot and Montesquieu fostered the Enlightenment, creating a need for a socio-economic equality that led to the revolution and the decline of the divine right monarchy.

On the 14 July 1789, the Parisians stormed the Bastille, symbol of the royal authority and on the 3 September 1791, the first written Constitution was created and approved by King Louis XVI. The King and ministers made up the executive branch and the Monarch was allowed a suspensive veto of the laws approved by the National Assembly.

On 10 August, 1792, the Parisians attacked the Tuileries Palace and the National Assembly suspended the King’s constitutional rights. The new parliament abolished the monarchy and proclaimed the Republic. As a consequence, on 17 August 1795, a new constitution was approved giving the executive power to a Directory.

Paris during Napoleon

The new Constitution was not accepted by monarchic groups and Jacobins. Several uprisings took place in Paris, but were all repressed by the army.

Nevertheless, on 9 November 1799, the army was unable to crush the coup d’état led by Napoleon Bonaparte, which overthrew the Directory and replaced it by the Consulate, Napoleon being First Consul.

During the following fifteen years, Napoleon enlarged the Place du Carrousel, built two Arcs de Triumphed, a column, several markets, the Paris bourse and a few slaughter houses.

The Napoleonic Wars – and with it the Empire of Napoleon – ended on 20 November 1815, after Napoleon had been defeated at the Battle of Waterloo, and the second Treaty of Paris of 1815 was signed.

Urban development

Once Napoleon had been defeated, France experienced great political uncertainty until Napoleon’s nephew organized a coup d’état in 1851 and became Emperor Napoleon III. During the following seventeen years, Napoleon III promoted the city’s urban development.

During this period and with Baron Haussmann as the prefect of Paris, the city changed its urban structure, rebuilding the center, knocking down its fortification and expanding the metropolitan territory.

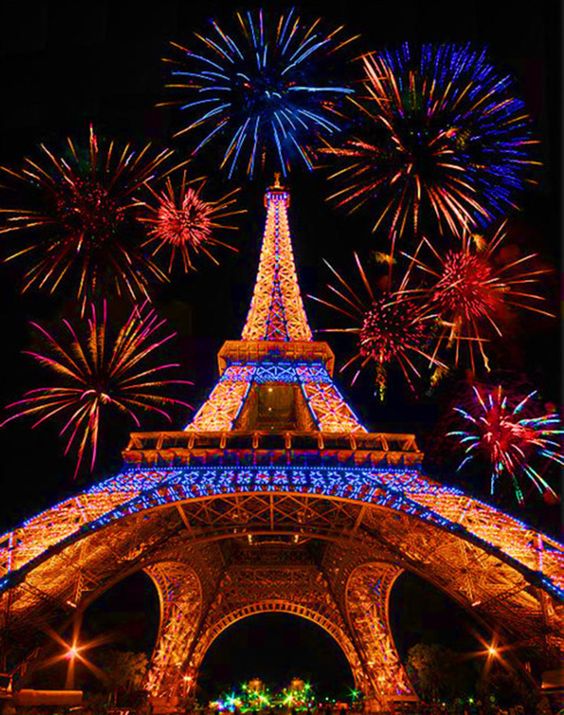

On the 28 January 1871, Paris was conquered by the Prussian troops and a few years later (at the end of 1800), the Third Republic was proclaimed. With the new government, an era of economic growth began for the city, promoting in 1889 the construction of the Eiffel Tower, worldwide symbol of Paris.

Contemporary Paris

From the twentieth century on, Paris suffered important changes with the reconstruction of different neighborhoods, many damaged during World War I and World War II.

During World War I, the city resisted the German offensives. However, in 1940, Paris was occupied by the Nazis, although the Parisians resisted and freed the capital on 25 August 1944.

During the war against Algeria, several violent manifestations took place in Paris against the war, with numerous attacks by the OAS (Organisation of the Secret Army).

During the months of May and June 1968, a series of protests took place in the capital of France, known as “May 68”. This was the largest student protest in the history of France and, possibly, the rest of Western Europe.

One of the last riots to take place in Paris was in March 2006, when students poured out onto the streets and protested against the labour market reform.

In November 2015, Paris witnessed a tragic event, several terrorist attacks hit the city and the suburbs of Saint-Denis, killing 137 people and injuring 415.

Romans and Schwyzerdüütsch (100BC - X Century)

Though human history in Zurich began before the Romans, it seems it was they who gave the city its name. Around 15 BC they established a military base at the site of today’s Lindenh of which was called Turicum, and as later inhabitants weren’t so fluent in Latin, it gradually became the slightly more callous ‘Zurich’. On Lindenh of you can find a copy of the Roman tomb stone mentioning Turicum. Roman rule ended around 400 AD and nobody really has any idea what went on in Zurich for the next few centuries. One important change that falls into this obscure period is the arrival of the Germanic tribe of the Allemanni, who brought with them the language that was to become today’s Swiss German dialect (Schwyzerdüütsch). By the 9th Century Zurich was part of the Carolingian empire and according to legend the emperor Charlemagne founded Zurich’s main cathedral, the Grossmünster. Maybe the man himself never actually turned up in Zurich, but the kings of the Franks did have a secondary residence, a pfalz, on the Lindenhof.

Zurich in women’s hands (XII-XIV Century)

In the 13th Century Zurich became an imperial city, answering only to the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire which had grown out of the Carolingian Empire. Formally Zurich was now headed by a woman - the abbess of the Fraumünster abbey, who however shared power with an elected reichsvogt, the emperor’s representative. In 1336 times began to change. An uprising of Zurich’s craftsmen made the newly founded guilds the foundation of Zurich’s political structure, weakening the power of the church and the landed gentry. Even today people who matter in Zurich belong to one of the zünfte (guilds) and the Sechseläuten procession in April is their celebration (see Basics for the exact date). Many of the guild houses, still in use today, are now also restaurants like the ZunfthausZurSchmiden or the Zunfthaus am Neumarkt.

Zurich goes Swiss… (XIV-XVI Century)

The guild revolution left Zurich a little isolated, which led to its alliance with the founding cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy in 1351. So Zurich joined ‘Switzerland’, which had existed as a treaty since 1291. This however didn’t stop the city waging war against fellow cantons, such as with Schwyz which got in the way of Zurich’s plans for territorial expansion. Soon the city ruled over lands all around Lake Zurich and north all the way to the Rhine and drew its wealth from craft production, trading across the Alps and the contracting of mercenaries to foreign powers. Soldiers from the Swiss cantons armed with pike and halberd were sought-after mercenaries who fought in all major armies in Europe - occasionally even against each other. They had gained a reputation as formidable fighters, due amongst other things to the victories of the Swiss cantons over the Habsburg king’s forces trying to rein them in. Mercenary service wasn’t appreciated by all though. It was connected to corruption and moral decay and came to be criticised more and more in the early 16th Century.

…and Protestant (XVI Century)

Huldrych Zwingli, priest at the Grossmünster, was one of the main critics of mercenary service. But he had a lot more to say on moral matters and became the initiator of the Reformation in Zurich from 1520 on. Apart from banning mercenary service, transferring properties of monasteries and convents to the city and removing decorations from churches, the Reformation meant an end to all frivolous behaviour - drinking, prostitution and actually most fun was forbidden or strictly regulated. This had a lasting effect on Zurich. Some other Swiss cantons followed suit and became Protestant while many remained Catholic - a rift which led to many future conflicts in the Confederacy.

Napoleon causes a little bother (XVI-XVIII Century)

During the 16th and 17th Centuries Zurich’s wealth and influence increased, making it confident enough to declare itself Republic of Zurich in 1648. While political power was increasingly monopolised by a few families, new ideas and debate flourished. Among the intellectuals of the time were the educational reformer Heinrich Pestalozzi, historian Johann JakobBodmer who had close ties to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, or the painter Johann Heinrich Füssli, whose work you’ll find today in the Kunsthaus. From 1780 onwards they might have read the NeueZürcherZeitung, Zurich’s top quality newspaper which still exists today. In 1798 Zurich lost its independence as Napoleon took over, transforming the Swiss Confederacy into the Helvetic Republic, a centralised puppet state which only survived for five years. In once again independent Zurich, political refugees from other parts of Europe found asylum giving momentum to liberal ideas which led in 1831 to the transformation of Zurich to a model liberal state. This meant more democratic structures, an end to the city’s domination over the surrounding countryside and an educational reform which resulted in the school houses on Rämistrasse.

Railways and radical workers (XIX-XX Century)

Modern-day Switzerland was founded in 1848 as a federation with much closer ties between the cantons than before. The year before, the first railway line in Switzerland was opened. Railways were also the business Alfred Escher was in, the man who for the next few decades dominated Zurich and Swiss politics like no other. Also known as the Tsar of Zurich, he founded large railway companies and was the mastermind of the construction of the Gotthard rail tunnel, finally connecting Italy with Switzerland and Germany in 1880. Escher’s statue can be found, not surprisingly, just in front of the main train station at the beginning of Bahnh of strasse. Switzerland remained neutral during the First World War and was refuge to the likes of James Joyce and the artists who started the Dada movement here. The war did however exacerbate the poverty of the working classes and in 1918 a socialist committee with close contacts to communist Russia called a general strike. The government reacted by sending in the army which clashed with demonstrators in Zurich and brought about the end of the strike. Many of the committee’s demands were fulfilled, though not the demand for the right of women to vote, which was not introduced until 1971(!).

The Réduit and the war (XX Century)

During most of the Second World War Switzerland, formally neutral, was totally surrounded by the Axis powers, making it difficult to import food and other goods. General Guisan prepared for a military attack by posting the army at the borders and literally hollowing out the Alps, envisaging a guerrilla war from the mountains, the so-called réduit strategy. From a traditional point of view this is what saved Switzerland from becoming part of Nazi Germany, but more recently historians have suggested that other factors may have been more important, sparking off intense and emotional public debate in the 1990s. Switzerland certainly was an important financial intermediary for the Nazis, allowed freight traffic between Germany and Italy and also supplied Germany with weapons parts.

Zurich today (XX-XXI Century)

After the war Switzerland’s economy boomed and mass immigration from Southern Europe set in, while culturally and politically Switzerland remained stoutly anti-communist and very conservative. In 1968 and 1980 youth movements clashed with police, rocking Zurich and finally leading to the establishment of several autonomous youth centres. The movement brought new ideas and new cultural life to Zurich, giving it much of the drive it has today and finally shaking off the puritan restrictions Zwingli had implanted. It also spawned Zurich’s ‘needle park’, the open drug scene on Platzspitz which made Zurich notorious across Europe in the early 1990s. While the official reaction was repressive at first, Zurich shaped Swiss drug politics, introducing innovative controlled heroin programs which got addicts off the streets. Today Zurich is still a major financial centre and has lost the conservative reputation. It has become popular as a place to live for highly-skilled workers from across Europe, since Switzerland signed free-movement agreements with the European Union in 1999. This has made the lack of affordable apartments one of the major topics in Zurich today.

Inclusions:

- Accommodation for 03 Nights in Swiss

- Accommodation for 03 Night in Paris

- Guided City Tour of Paris.

- Orientation Tour of Interlaken, Lucerne

- Paris Eiffel Tower Level 2

- Paris Seine River Cruise

- Zurich Mt. Titlis

- 06 Breakfast and 06 Veg / Non Veg / Jain Dinners at Indian Restaurant

- New Year's Eve Gala Dinner with 2 hrs free flow of Wine, Beer, Vodka, Whiskey Black Lable, Juices & Much more.

- Hindi / English speaking Tour Leader / Manager throughout the tour

- Airport Pickup and Drop (Between 10 AM to 07 PM)

Exclusions:

- Air Tickets

- Visa and Insurance

- Extra charges/expenses of personal nature like laundry, mineral water/drinks, telephone or any other charges/ expenses not mentioned in Inclusions Optional Tours

- Mandatory tips of Euro 2 per person per day for Coach Drivers, Guides etc.

Hotel Details:

|

Destination |

Hotel Details |

|

ZURICH |

|

|

PARIS |

Holiday Inn CDG Express or Similar |

Costing:

|

Adult Cost on Twin / Double / Triple |

€ 1050 PP |

|

Single Supplement |

€ 345 PP |

|

Child with Bed (3 - 11Years) |

€ 900 PC |

|

Child without Bed (3 - 11Years) |

€ 680 PC |

|

Infant (0 - 2 Years) |

€ 200 PC |

Optional Services

- Disneyland Ticket 1 Day 1 Park @ 90 Euro PP

- Disneyland Ticket 1 Day 1 Park with Transfer (Min. 8 Pax) 130 Euro PP

- Disneyland Ticket 1 Day 2 Park @ 115 Euro PP

- Disneyland Ticket 1 Day 2 Park with Transfer (Min. 8 Pax) 155 Euro PP

- Disneyland Return Transfer @ 200 Euro (2 Pax to 7 Pax ) Per Van

- Paris by Night with Transfer** @ 30 Euro

- Lido Show without transfer @ 100 Euro

- Louvre Museum without transfer @ 25 Euro

- Top of Europe - Mt. Jungfrau with transfer @ 149 Euro

The history of Paris dates back to approximately 259 BC, with the Parisii, a Celtic tribe settled on the banks of the Seine. In 52 BC, the fishermen village was conquered by the Romans, founding a Gallo-Roman town called Lutetia.

The city changed its name to Paris during the fourth century. During this period, the city was threatened by Attila the Hun and his army, and according to the legend, the inhabitants of Paris resisted the attacks thanks to the providential intervention of Saint Geneviève (patron saint of the city).

In 508 the first king of the Franks, Clovis I, made Paris the capital of his empire. In 987, the Capetian dynasty came to power until 1328.

During the eleventh century, Paris gradually became more prosper thanks to its trade in silver and because it was a strategic route for pilgrims and traders.

Riots and uprisings

At the beginning of the twelfth century, the first university in France was founded thanks to the uprisings of students and professors. Louis IX appointed the chaplain, Robert de Sorbon, to establish the College, which was later named after him, the Sorbonne.

Three insurrections took place during the fourteenth century in Paris: the first, in 1358, when Étienne Marcel led a merchant revolt. The second was a tax riot known as the Maillot uprising in 1382, and the third was the Cabochien revolt in 1413. These riots were part of the Hundred Years’ War.

Additionally, the capital of France, which was the most populated city in Europe in 1328, was struck by the Bubonic plague, killing thousands of Parisians. Following the Hundred Years’ War, Paris was devastated and Joan of Arc was unable to keep the British from taking Paris. In 1431, Henry VI of England was crowned King of France and the English did not leave until 1436.

The city kept on growing during the following centuries, although monarchs preferred to live in the Loire Valley. In 1528, King Francis I returned the royal residence to Paris and the city became the largest in Western Europe.

On 24 August, 1572, the royal council decided to assassinate the leaders of the Protestants (Hugonotes), which lead to Catholic mobs butchering protestants in Paris. Known as St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, it spread from Paris to the rest of the country during the following months.

Margaret of Valois, sister of King Charles IX, married Henri of Navarre (Head of the Huguenots dynasty) that same year, while Henry III tried to find a solution to the conflicts between the Catholics and Protestants. However, in 1588, the French Catholics forced Henry III to flee on the so-called Day of the Barricades and killed him a year later. He was succeeded by Henry of Navarre, becoming King Henry IV. A decade later, Henry IV decided to convert to Catholicism and was crowned King of France in 1594.

In 1648, the second Day of the Barricades took place when the Parisians opposed the King due to the deplorable level of poverty. This was the beginning of a long uprising called the Fronde parlementaire, a serie of civil wars that took place in France between 1648 and 1662. Fifteen years later, King Louis XVI moved the royal residence to Versailles.

The decline of the Monarchy

As a consequence of the Fronde, poverty spread throughout Paris. During this period, there was an explosion of the Enlightenment philosophical movement, whose principles are based on reason, equality and freedom.

Philosophers and authors such as Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot and Montesquieu fostered the Enlightenment, creating a need for a socio-economic equality that led to the revolution and the decline of the divine right monarchy.

On the 14 July 1789, the Parisians stormed the Bastille, symbol of the royal authority and on the 3 September 1791, the first written Constitution was created and approved by King Louis XVI. The King and ministers made up the executive branch and the Monarch was allowed a suspensive veto of the laws approved by the National Assembly.

On 10 August, 1792, the Parisians attacked the Tuileries Palace and the National Assembly suspended the King’s constitutional rights. The new parliament abolished the monarchy and proclaimed the Republic. As a consequence, on 17 August 1795, a new constitution was approved giving the executive power to a Directory.

Paris during Napoleon

The new Constitution was not accepted by monarchic groups and Jacobins. Several uprisings took place in Paris, but were all repressed by the army.

Nevertheless, on 9 November 1799, the army was unable to crush the coup d’état led by Napoleon Bonaparte, which overthrew the Directory and replaced it by the Consulate, Napoleon being First Consul.

During the following fifteen years, Napoleon enlarged the Place du Carrousel, built two Arcs de Triumphed, a column, several markets, the Paris bourse and a few slaughter houses.

The Napoleonic Wars – and with it the Empire of Napoleon – ended on 20 November 1815, after Napoleon had been defeated at the Battle of Waterloo, and the second Treaty of Paris of 1815 was signed.

Urban development

Once Napoleon had been defeated, France experienced great political uncertainty until Napoleon’s nephew organized a coup d’état in 1851 and became Emperor Napoleon III. During the following seventeen years, Napoleon III promoted the city’s urban development.

During this period and with Baron Haussmann as the prefect of Paris, the city changed its urban structure, rebuilding the center, knocking down its fortification and expanding the metropolitan territory.

On the 28 January 1871, Paris was conquered by the Prussian troops and a few years later (at the end of 1800), the Third Republic was proclaimed. With the new government, an era of economic growth began for the city, promoting in 1889 the construction of the Eiffel Tower, worldwide symbol of Paris.

Contemporary Paris

From the twentieth century on, Paris suffered important changes with the reconstruction of different neighborhoods, many damaged during World War I and World War II.

During World War I, the city resisted the German offensives. However, in 1940, Paris was occupied by the Nazis, although the Parisians resisted and freed the capital on 25 August 1944.

During the war against Algeria, several violent manifestations took place in Paris against the war, with numerous attacks by the OAS (Organisation of the Secret Army).

During the months of May and June 1968, a series of protests took place in the capital of France, known as “May 68”. This was the largest student protest in the history of France and, possibly, the rest of Western Europe.

One of the last riots to take place in Paris was in March 2006, when students poured out onto the streets and protested against the labour market reform.

In November 2015, Paris witnessed a tragic event, several terrorist attacks hit the city and the suburbs of Saint-Denis, killing 137 people and injuring 415.

Romans and Schwyzerdüütsch (100BC - X Century)

Though human history in Zurich began before the Romans, it seems it was they who gave the city its name. Around 15 BC they established a military base at the site of today’s Lindenh of which was called Turicum, and as later inhabitants weren’t so fluent in Latin, it gradually became the slightly more callous ‘Zurich’. On Lindenh of you can find a copy of the Roman tomb stone mentioning Turicum. Roman rule ended around 400 AD and nobody really has any idea what went on in Zurich for the next few centuries. One important change that falls into this obscure period is the arrival of the Germanic tribe of the Allemanni, who brought with them the language that was to become today’s Swiss German dialect (Schwyzerdüütsch). By the 9th Century Zurich was part of the Carolingian empire and according to legend the emperor Charlemagne founded Zurich’s main cathedral, the Grossmünster. Maybe the man himself never actually turned up in Zurich, but the kings of the Franks did have a secondary residence, a pfalz, on the Lindenhof.

Zurich in women’s hands (XII-XIV Century)

In the 13th Century Zurich became an imperial city, answering only to the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire which had grown out of the Carolingian Empire. Formally Zurich was now headed by a woman - the abbess of the Fraumünster abbey, who however shared power with an elected reichsvogt, the emperor’s representative. In 1336 times began to change. An uprising of Zurich’s craftsmen made the newly founded guilds the foundation of Zurich’s political structure, weakening the power of the church and the landed gentry. Even today people who matter in Zurich belong to one of the zünfte (guilds) and the Sechseläuten procession in April is their celebration (see Basics for the exact date). Many of the guild houses, still in use today, are now also restaurants like the ZunfthausZurSchmiden or the Zunfthaus am Neumarkt.

Zurich goes Swiss… (XIV-XVI Century)

The guild revolution left Zurich a little isolated, which led to its alliance with the founding cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy in 1351. So Zurich joined ‘Switzerland’, which had existed as a treaty since 1291. This however didn’t stop the city waging war against fellow cantons, such as with Schwyz which got in the way of Zurich’s plans for territorial expansion. Soon the city ruled over lands all around Lake Zurich and north all the way to the Rhine and drew its wealth from craft production, trading across the Alps and the contracting of mercenaries to foreign powers. Soldiers from the Swiss cantons armed with pike and halberd were sought-after mercenaries who fought in all major armies in Europe - occasionally even against each other. They had gained a reputation as formidable fighters, due amongst other things to the victories of the Swiss cantons over the Habsburg king’s forces trying to rein them in. Mercenary service wasn’t appreciated by all though. It was connected to corruption and moral decay and came to be criticised more and more in the early 16th Century.

…and Protestant (XVI Century)

Huldrych Zwingli, priest at the Grossmünster, was one of the main critics of mercenary service. But he had a lot more to say on moral matters and became the initiator of the Reformation in Zurich from 1520 on. Apart from banning mercenary service, transferring properties of monasteries and convents to the city and removing decorations from churches, the Reformation meant an end to all frivolous behaviour - drinking, prostitution and actually most fun was forbidden or strictly regulated. This had a lasting effect on Zurich. Some other Swiss cantons followed suit and became Protestant while many remained Catholic - a rift which led to many future conflicts in the Confederacy.

Napoleon causes a little bother (XVI-XVIII Century)

During the 16th and 17th Centuries Zurich’s wealth and influence increased, making it confident enough to declare itself Republic of Zurich in 1648. While political power was increasingly monopolised by a few families, new ideas and debate flourished. Among the intellectuals of the time were the educational reformer Heinrich Pestalozzi, historian Johann JakobBodmer who had close ties to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, or the painter Johann Heinrich Füssli, whose work you’ll find today in the Kunsthaus. From 1780 onwards they might have read the NeueZürcherZeitung, Zurich’s top quality newspaper which still exists today. In 1798 Zurich lost its independence as Napoleon took over, transforming the Swiss Confederacy into the Helvetic Republic, a centralised puppet state which only survived for five years. In once again independent Zurich, political refugees from other parts of Europe found asylum giving momentum to liberal ideas which led in 1831 to the transformation of Zurich to a model liberal state. This meant more democratic structures, an end to the city’s domination over the surrounding countryside and an educational reform which resulted in the school houses on Rämistrasse.

Railways and radical workers (XIX-XX Century)

Modern-day Switzerland was founded in 1848 as a federation with much closer ties between the cantons than before. The year before, the first railway line in Switzerland was opened. Railways were also the business Alfred Escher was in, the man who for the next few decades dominated Zurich and Swiss politics like no other. Also known as the Tsar of Zurich, he founded large railway companies and was the mastermind of the construction of the Gotthard rail tunnel, finally connecting Italy with Switzerland and Germany in 1880. Escher’s statue can be found, not surprisingly, just in front of the main train station at the beginning of Bahnh of strasse. Switzerland remained neutral during the First World War and was refuge to the likes of James Joyce and the artists who started the Dada movement here. The war did however exacerbate the poverty of the working classes and in 1918 a socialist committee with close contacts to communist Russia called a general strike. The government reacted by sending in the army which clashed with demonstrators in Zurich and brought about the end of the strike. Many of the committee’s demands were fulfilled, though not the demand for the right of women to vote, which was not introduced until 1971(!).

The Réduit and the war (XX Century)

During most of the Second World War Switzerland, formally neutral, was totally surrounded by the Axis powers, making it difficult to import food and other goods. General Guisan prepared for a military attack by posting the army at the borders and literally hollowing out the Alps, envisaging a guerrilla war from the mountains, the so-called réduit strategy. From a traditional point of view this is what saved Switzerland from becoming part of Nazi Germany, but more recently historians have suggested that other factors may have been more important, sparking off intense and emotional public debate in the 1990s. Switzerland certainly was an important financial intermediary for the Nazis, allowed freight traffic between Germany and Italy and also supplied Germany with weapons parts.

Zurich today (XX-XXI Century)

After the war Switzerland’s economy boomed and mass immigration from Southern Europe set in, while culturally and politically Switzerland remained stoutly anti-communist and very conservative. In 1968 and 1980 youth movements clashed with police, rocking Zurich and finally leading to the establishment of several autonomous youth centres. The movement brought new ideas and new cultural life to Zurich, giving it much of the drive it has today and finally shaking off the puritan restrictions Zwingli had implanted. It also spawned Zurich’s ‘needle park’, the open drug scene on Platzspitz which made Zurich notorious across Europe in the early 1990s. While the official reaction was repressive at first, Zurich shaped Swiss drug politics, introducing innovative controlled heroin programs which got addicts off the streets. Today Zurich is still a major financial centre and has lost the conservative reputation. It has become popular as a place to live for highly-skilled workers from across Europe, since Switzerland signed free-movement agreements with the European Union in 1999. This has made the lack of affordable apartments one of the major topics in Zurich today.